Putting the Tea back in New Jersey

I figure the plant New Jersey Tea is ironically named. I've been mildly obsessed with the plant for seven or eight years but have only seen it in three different places here in my home state. I once asked an elder botanist about New Jersey Tea, and she said "Oh, it's pretty common... outside of New Jersey!"

New Jersey Tea (Ceanothus americanus) is a multi-stemmed shrub that rarely exceeds 3' or so in height. While it may have been formerly common here in north Jersey, two factors seem to have conspired against its widespread persistence in the current flora.

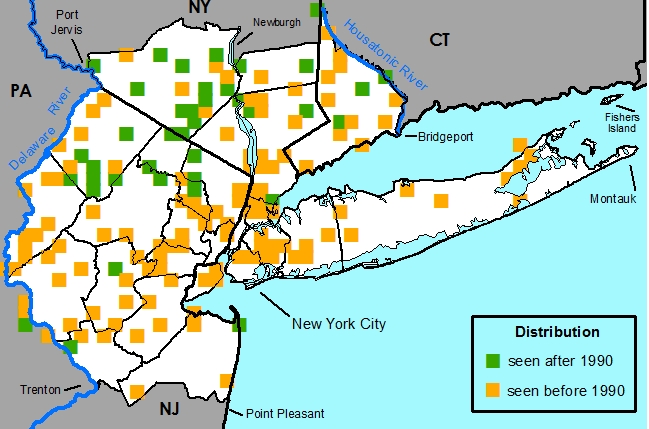

Distribution map for Ceanothus americanus, from the New York Metropolitan Flora Project

The first is the overabundance of deer, for which New Jersey Tea offers choice forage. Unlike many other shrubs, it never gets above browsing height, but always offers its succulent fresh growth and foamy white blooming panicles at an ideal level for hungry ungulates.

The second factor relates to New Jersey Tea's need for occasional fire to stimulate recruitment and reduce competition.

* * *

I once asked Karl Anderson, an elder botanist and a generous teacher, about Ceanothus americanus populations in New Jersey. He looked through his (copious, well-organized) field notes and pointed me in the direction of a location where he had last seen the plant.

At first, the locale was elusive. Karl's site description referenced a bridge that no longer existed, and a village name that was known only in the immediate vicinity.

Nevertheless, some online research and a bit of conjecture had Rachel and I driving along a small highway by the Delaware River, with my head out of the window looking up the sides of red shale bluffs for nearly extirpated small shrubs with frothy white blooms. (Watch out for driveby botanizers!)

Improbably, perhaps, we found our mark. In the voice memo I recorded on the spot, I hear my two year-old son Beren warbling from the car seat in the background, and the following rough directions:

"110 paces north of a falling rock sign that is north of a 50 mph sign, a double-trunk cedar hanging off the bluff among box elders. Clamber up that cedar and there's a small colony of Ceanothus up there. 35 paces north of that is a tall inaccessible bluff with some New Jersey Tea plants on it, and then just beyond that is an angle cut between a Norway maple and a young sycamore tree, with lots of Helianthus divaricatus at the base. At least one plant is in flower there."

When I excitedly returned, hoping to collect a few seeds later that summer, I found that deer had gotten to even the most inaccessible-seeming plants and browsed most of the flowers before seed set.

Along the Delaware River bluffs

* * *

To learn more about New Jersey Tea, I went to visit ecologist Roger Latham at the Pink Hill serpentine barrens at the Tyler Arboretum in southeastern Pennsylvania.

The "barrens" is a three-acre remnant grassland. I say remnant because as recently as the 1930s it occupied over a dozen acres. Further, it was one of eight serpentine barrens within less than five linear miles of one another. However, the other seven have been destroyed and so Pink Hill now stands alone, significantly isolated from the next closest extant barrens.

The designation "serpentine" relates not to some undulating topography as I guessed when first hearing the term, but to the unusual serpentinite geology that underlies the barrens.

"Grassland and the other plant communities that make up serpentine barrens live on thin soils overtop a geologic oddity, a metamorphic, greenish rock [i.e. serpentinite] formed in deep cracks on the seafloor"[i]

Latham showed me some newly exposed bedrock in areas of the barrens subject to an experimental topsoil removal practice. The freshly oxidized magnesium was beautifully seafoam green on the slabs of bedrock.

Serpentinite is an ultramafic rock, one with extremely high levels of magnesium as well as high levels of nickel and chromium, and a severe deficiency of calcium. The innate toxicity of this geology to plants seems to give an advantage to specialist species adapted for adverse conditions, while disadvantaging some common, generalist species.

Latham has made a case for the antiquity of the plant community of the serpentine barrens by documenting the number of rare plant species at Pink Hill (both extant and historically documented). As it turns out, a number of unusual species at the barrens are at the edge of their range and hail from "the drier Midwest, or in the hotter South, or... the sandy Atlantic Coastal Plain. The ranges of a few even extend into the Southwestern deserts and parts of Mexico." (Latham 2008)

As with relict prairie species elsewhere in the northeast, these species may have migrated into the area during a warm spell after the last glaciation, beginning about 8,000 years ago. The persistence into the present era of these unusual grassland species seems most readily ascribed to Native American burning. Fires set by indigenous people would have maintained large treeless areas and thin soils over the special geology of the serpentine barrens. The toxicity of the soil may have maintained the barrens as a natural community (rather than an agricultural field) during the colonial farming era.

It was within the context of this exceptional (in fact, globally rare) plant community that I saw my first significant population of New Jersey Tea, an impressive (to me at least) sward in copious seed as we entered the grassland and ascended a mild slope.

Part of the reason that New Jersey Tea is thriving on the site may be the contemporary history of controlled burns at Pink Hill. Tyler Arboretum staff began managing the site with fire in the 1970s, and the practiced continued through to the present, with burns in 2004 and 2008.

* * *

Since my first foray in search of Ceanothus along the shale bluffs near the Delaware River, I've seen the species at a few other places in New Jersey.

One occurrence was along an open utility corridor in a large forested area in Morris County, with glade species such as hoary mountain mint, upland boneset, and Carolina rose fairly nearby. The area was semi-shaded, on an exposed, rocky area of shallow soil.

Along a nearby roadside was another occurrence, with sassafras, Oriental bittersweet, mockernut hickory, poison ivy, blackcap raspberry, and multiflora rose growing nearby. It was growing along the road at base of a small wooded hill with a south-facing aspect. Plants in the nearby woods included such "rich" woodland species as stoneroot, purple-node Joe Pye, white doll's eyes, and spicebush.

A third location was next to a small bridge encircling a dammed lake in a north Jersey state park.

Taken as an aggregate, all the occurrences had in common rocky, well-drained soils, possibly with a bit of richness (i.e. not strictly acidic poor soils), and areas of at least partial sunlight.

A roadbank in North Carolina, 2016

* * *

What would bring New Jersey Tea back to New Jersey?

Probably the widespread use of fire as a management tool in our forests.

A passage about western species of Ceanothus (the center of diversity for the genus is in California) in the excellent textbook Forest Ecosystems[ii] is suggestive of the penchant of the genus to rise phoenix-like from the seedbank after fire:

"[C]lear-cutting and broadcast-burning old-growth Douglas Fir forests, some up to eight hundred years old, often leads to a thick cover of nitrogen-fixing shrubs in the genus Ceanothus. Seeds of these species have persisted in the soil since the previous early succession, hundreds of years ago, and are triggered to germinate by the heat of the broadcast burn." (p. 123)

I often wonder whether the many species of (now) rare or locally extirpated plants (of many different genera) might someday spontaneously return to our much-diminished forests here in New Jersey. Whether there are seeds just below the duff, waiting to be stirred into growth by some (magic?) trigger. In the case of many of our forest herbs, the answer may be no. Species like trilliums, trout lily and Solomon's seal do not appear to have long-lived seed[iii].

In the case of Ceanothus, however, the species might lie in wait for a significant disturbance event for close to a millenium!

The data on Ceanothus americanus seems to suggest a similar lifeway to that of its western congeners. One study found it to be about twice as frequent on burned vs. unburned oak woodlands in central New York. Likewise, it is described as a "conspicuous dominant" among prairie grasses where fires are frequent.[iv]

In some smaller way, we've seen this confirmed in our nursery practice. I'll usually pre-treat Ceanothus seed by putting it in water just past the boil. This seems to stimulate high levels of (and sometimes very rapid) germination, though some years have been better than others for us.

* * *

What's good for New Jersey Tea may be good for a lot of species in the state, including a significant number of rarities. It strikes me that many of the species I've searched for in New Jersey, sometimes in vain, are species that occur in that interesting middle ground which is neither closed-canopy mature forest nor ruderal, over-enriched post-agricultural oldfield.

The species I have in mind include gentians, perennial sunflowers, Virginia snakeroot, Indian paintbrush, some mountain mint species, a host of lesser-known asters like wavyleaf aster and late purple aster, unusual and/or rare milkweeds like purple milkweed, fourleaf milkweed, whorled milkweed, green milkweed, and many others besides.

I think of these species as glade species, or sometimes as prairie outliers, or as thicket, savannah or even grassland species. The commonality between them is that they thrive in habitats with an open or absent tree canopy, and probably in areas with some type of intact natural soil dynamics (as opposed to the highly anthropogenic soils associated with farm fields).

Roger Latham, in a study of Pennsylvania remnant grassland, meadow, and savannah habitats[v], lists 259 state-listed species with fidelity to those habitat types. While no similar tally has been performed for New Jersey's flora, I suspect that a high number of state rarities would likewise be found to be species of open, high-quality habitats.

* * *

Significant parts of what used to be the Pink Hill Barrens have succeeded to forest, pretty generic second-growth forest with red maples, black locust, greenbrier, multiflora rose, Japanese honeysuckle, Japanese stiltgrass and so on.

In the midst of this succession from rare barrens habitat to middling forest habitat, an interesting restoration technique was being utilized at Pink Hill to reclaim areas of barrens vegetation.

Roger Latham described hiring an "artistic operator" with a front-end loader to scrape the surface topsoil off and remove it in a dump truck. With the mineral soils and beautiful green serpentinite bedrock exposed, there has been a flush of germination from the seedbank, as well as seeding in from adjacent areas of intact barrens vegetation.

To my eye, the thin soils over bedrock appeared to be supporting small, noncompetitive plants -- the kind of specialists that would not compete in a richer, deeper, more "average" soil.

Leaving the Barrens that day, the promise of fire and topsoil removal in revealing the true identity of a place, with its characteristic flora, was etched in my mind.

I thought about the implications for my home state. If New Jersey could have its New Jersey Tea restored, in the process New Jersey itself might return to its full, place-based character and identity. A land of diverse geologies and forest structure, a state where fire and stone bring forth the abundant white blooms of Ceanothus americanus and many others besides.

In our native permaculture garden at Wild Ridge Farm

_______________________________________________________________________________

[i] Latham, R. Pink Hill Serpentine Barrens Restoration and Management Plan. (2008)

[ii] Perry et al. Forest Ecosystems, 2nd Ed. (2008)

[iii] Leckie et al. "The seed bank in an old-growth, temperate deciduous forest". Can. J. Bot. 78: 181–192 (2000)

[iv] Coladonato, Milo. 1993. Ceanothus americanus. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2016, November 26].

[v] Latham, R and Thorne, J. F. Keystone Grasslands: Restoration and Reclamation of Native Grassland, Meadow, and Savannah in Pennsylvania State Parks and State Game Lands. (2007)